The notes for the works on tonight's programme are organised chronologically through Clara Schumann’s creative periods.

Lieder texts: Translation © Richard Stokes, author of: The Book of Lieder (Faber), provided via Oxford International Song Festival (www.oxfordsong.org).

Programme notes researched and written by Stephanie Nicholls for Mirabilis Collective.

Quatre Pièces fugitives, Op. 15 (1840)

No. 1 - Larghetto | No. 2 - Un poco agitato

Clara Schumann composed her Quatre Pièces fugitives in 1840, shortly after her marriage to Robert Schumann. Published five years later, these intimate character pieces represent some of her most personal musical statements from the early years of her marriage.

When the work appeared in 1845, a review in the influential Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung praised Clara's distinctive voice: "Clara Schumann's writing contains a number of original traits. She is far removed from merely copying Chopin, Mendelssohn or Robert Schumann. At the most, these masters sometimes shine through the particular colouring characteristic of all of Clara Schumann's pieces. The Quatre Pièces fugitives all differ in character and style."¹

The opening Larghetto is sweetly reflective, demonstrating Clara's gift for creating intimate musical poetry. Her trademark improvisatory style flows naturally through each phrase, with melodies that seem to emerge spontaneously yet reveal careful compositional craft upon closer examination.

The second piece, Un poco agitato, shifts to more restless energy with lines that rise and fall like emotional conversations. The 1845 critic particularly noted how each piece maintains its individual character while contributing to the overall unity of the set.

Recent scholarship has revealed how Clara achieved this unity through subtle cyclic elements—recurring motifs and structural relationships that bind the four pieces into a cohesive whole.² This sophisticated approach to musical architecture demonstrates that these seemingly spontaneous works represent Clara's mature understanding of both small-scale form and large-scale design, proving that her compositional gifts extended well beyond the brilliant pianism for which she was famous.

Liebst du um Schönheit, Op. 12 No. 4 (Friedrich Rückert, 1841)

If you love for beauty

Programme Notes and Artist Biographies

Clara's most beloved song emerged from one of the most touching collaborative projects in music history. In 1841, Robert had composed nine songs to poems from Friedrich Rückert's Liebesfrühling (Love's Springtime) and urged Clara to contribute settings of her own. Writing while pregnant with their first child, Marie, Clara initially struggled, confessing in their shared diary: "With composition nothing at all is happening—sometimes I'd like to knock myself on my dumb head!"³

However, by June she had completed four Rückert settings, gifting them to Robert for his birthday. Robert secretly arranged for publication of twelve songs in total—nine of his, three of Clara's—presenting the collection to Clara as a surprise first anniversary gift. The work appeared under joint opus numbers (Op. 37/12), with Robert deliberately omitting any indication of which composer wrote which song, fulfilling his romantic vision that "posterity shall regard us as one heart and one soul."

"Liebst du um Schönheit" stands as Clara's most famous song, setting Rückert's four-stanza poem about true love versus superficial attractions. The protagonist pleads with their beloved to love authentically, rejecting false values of beauty, youth, and wealth in favour of genuine affection. Clara's musical setting perfectly captures the poem's direct simplicity while adding sophisticated harmonic touches that reveal her pianistic background.

The song employs modified strophic form, with each verse subtly varied to reflect the text's emotional progression. Clara's piano writing provides warm, flowing accompaniment that never overpowers the vocal line, demonstrating her understanding that in Lieder, the music must serve the poetry. The melody floats effortlessly above the accompaniment with natural motion that makes the song immediately appealing to both performers and audiences.

Scholars have noted how this "perfect" song reflects Clara's own psychological makeup—"a mixture of uncertainty and confidence"⁴—and demonstrates her ability to weave an entire composition from tiny motivic cells, much like her studies of Bach had taught her. The song's enduring popularity stems from its universal message about authentic love and Clara's gift for creating music that speaks directly to the heart.

This song, more than any other, established Clara's reputation as a composer of Lieder and became a staple of her concert programmes throughout her performing career.

Sechs Lieder, Op. 13 (1840-1843)

No. 1 - "Ich stand in dunkeln Traumen" (Heinrich Heine, 1840)

I stood darkly dreaming

No. 2 - "Sie liebten sich beide" (Heinrich Heine, 1842)

They loved one another

No. 3 - "Liebeszauber" (Emanuel Geibel, 1842)

Love's magic

No. 4 - "Der Mond kommt still gegangen" (Emanuel Geibel, 1843)

The moon rises silently

No. 5 - "Ich hab' in deinem Auge" (Friedrich Rückert, 1843)

I saw in your eyes

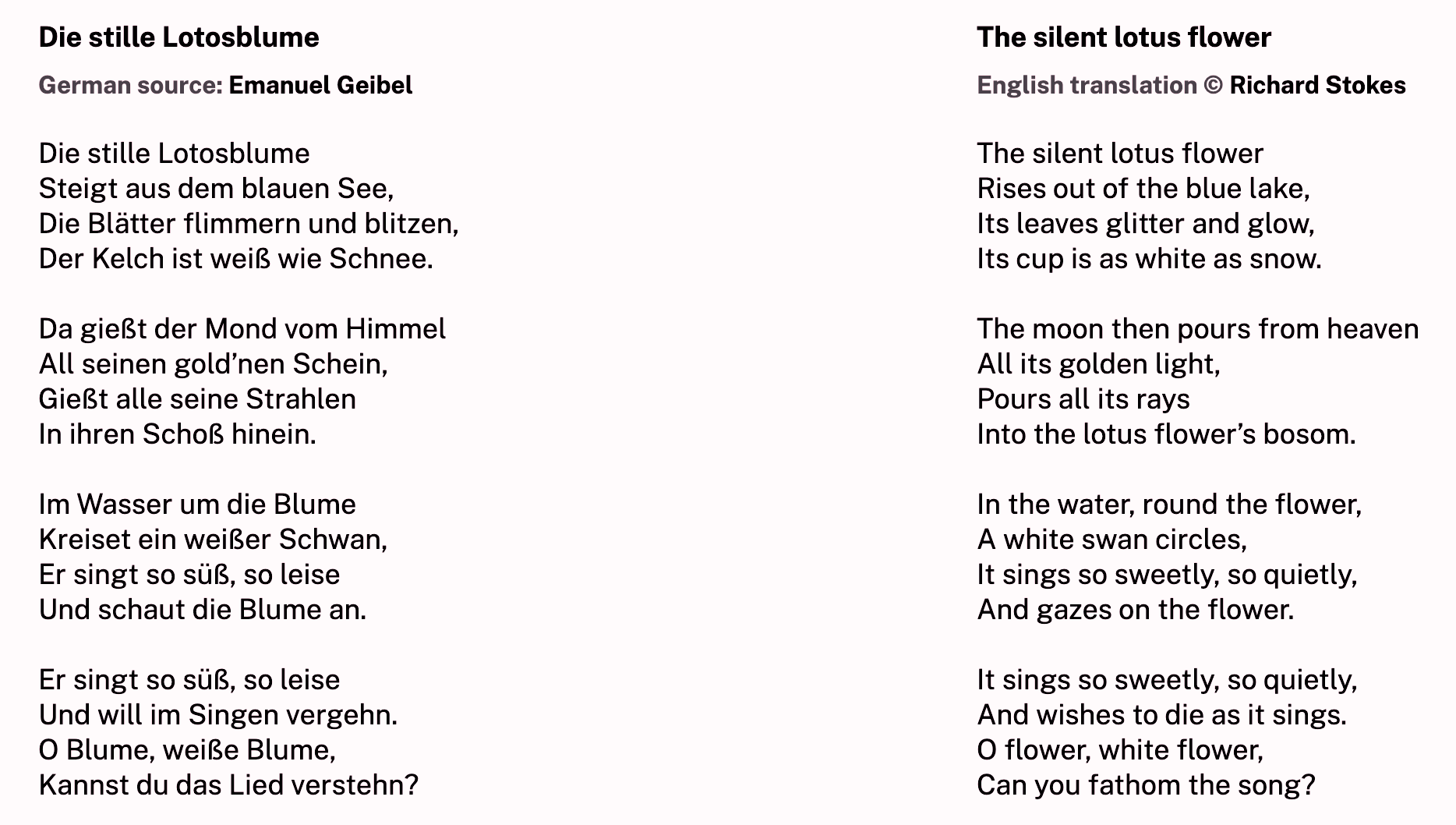

No. 6 - "Die stille Lotosblume" (Emanuel Geibel, 1843)

The silent lotus flower

Clara's Op. 13 song cycle represents the flowering of her creative partnership with Robert and her mastery of the German Lied tradition. Almost every song in her output was written as a Christmas or birthday gift for her husband, and these settings explore the themes beloved by German Romantics: love, yearning, melancholy, separation, and the mysteries of nature.

"Ich stand in dunkeln Traumen" is actually a revised version of an earlier Heine setting called "Ihr Bildnis," written as a Christmas present to Robert in 1840. The transformation between versions offers fascinating insight into Clara's compositional process—the later version being more conventional, while the first was characteristically bolder.

The two Heine songs showcase Clara's ability to convey the poet's dark emotions through spare, economical piano writing. "Sie liebten sich beide" tells of lovers who died without confessing their feelings—a tragic and enigmatic poem that Clara sets with haunting restraint.

The Geibel settings demonstrate her gift for capturing the innate musicality of his texts. "Liebeszauber" is a paean to love and nature, with Clara's piano writing displaying the brilliant accompaniments one might expect from a virtuoso while never overpowering the poetic meaning. "Der Mond kommt still gegangen" creates an atmosphere of nocturnal mystery through modified strophic form.

"Ich hab' in deinem Auge," a Rückert setting, was Clara's gift to Robert on his thirty-third birthday—a heartfelt musical declaration of love's constancy. "Die stille Lotosblume" concludes the cycle with Geibel's imagery of the lotus flower rising from the lake, bathed in moonlight—a perfect metaphor for the delicate beauty that emerges from Clara's musical language.

Clara used these songs regularly in her concert programmes, usually performed by colleagues with "Madame Schumann" at the piano. They employ unexpected harmonies and irregular rhythmic patterns to underscore her careful reading of each poet's words.

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 7 (1833-1835)

Second Movement - Romanze (Andante non troppo, con grazia)

Clara's Piano Concerto, begun when she was thirteen and premiered at sixteen under Mendelssohn's baton, represents one of the most remarkable compositional achievements by any teenage composer. The Romanze is perhaps the work's most revolutionary movement—a conversation between piano and solo cello with the orchestra completely silent.

Set in A-flat major (a warm, veiled key a semitone below the work's home key), this movement transforms the concerto experience into something intimate and chamber-like. Clara writes what amounts to an aria without words, with long, breathing phrases shaped by bel canto inflection. The balance between piano and cello—who leads, who listens—creates genuine musical dialogue at concerto scale.

This innovation was decades ahead of its time. When Brahms featured a similar cello solo in the slow movement of his Second Piano Concerto nearly fifty years later, he was paying direct homage to Clara's pioneering vision. In 1835, the idea of a tacit orchestra ceding the stage to piano and a single orchestral colleague was strikingly original—"a work that stands on its own, with no equivalent," as contemporary critics noted.

The movement's through-composed design links seamlessly to both the stormy first movement and dancing finale, creating a unified musical journey that influenced the structural thinking of Robert Schumann, Liszt, and later Romantic composers.

Piano Trio in G minor, Op. 17 (1846)

Second Movement - Scherzo (Tempo di minuetto) | Third Movement - Andante

Clara's Piano Trio is widely regarded as her finest compositional achievement. Written during a particularly challenging period when she was caring for her fourth child while Robert suffered from declining mental health, the work demonstrates extraordinary artistic maturity and technical accomplishment.

The Scherzo is marked unusually as "Tempo di minuetto," creating a rustic piece filled with snap rhythms carried by the violin. Clara's sophisticated handling of metre becomes evident in the Trio section, which plays across-the-bar metrical games reminiscent of Beethoven, with an expansive transition back to the main material.

The Andante serves as the work's emotional heart—a lovely instrumental song in G major that balances tender lyricism with a fierce contrasting middle section in E minor. This movement particularly impressed Clara's contemporaries, including Mendelssohn, who owned the score and praised its craftsmanship.

Clara completed the trio in September 1846, writing in her diary after the first rehearsal: "There is nothing greater than the joy of composing something oneself, and then listening to it." (October 2, 1846). The work was intended as a gift for Fanny Mendelssohn-Hensel, but Fanny died before publication, so Clara removed the dedication.

The trio's influence extended beyond Clara's immediate circle. Robert composed his first piano trio the following year, directly influenced by Clara's formal innovations and expressive language. Modern scholars note that "Clara's trio should be praised or criticised using the same guidelines as the trios of her contemporaries"—and by those standards, it stands among the finest chamber works of the mid-nineteenth century.

Three Romances for Violin and Piano, Op. 22 (1853)

No. 1 - Andante molto | No. 2 - Allegretto

Clara's Three Romances for Violin and Piano were among her final compositional efforts, written during the productive summer of 1853 when twenty-year-old Brahms first visited the Schumann household. Dedicated to violinist Joseph Joachim, these pieces became regular features of Clara and Joachim's concert tours, including a performance before King George V of Hanover, who declared them a "marvellous, heavenly pleasure."

The Andante molto contains hints of gypsy pathos amid lyrically supple sentiments—Clara's response to the Romantic fascination with Hungarian and Eastern European musical styles. Her writing demonstrates perfect balance between the violin's lyrical capabilities and the piano's harmonic richness.

The Allegretto maintains merry spirits while concealing a darker emotional centre, typical of Clara's sophisticated approach to the Romance genre. Contemporary critics praised how "all three pieces display an individual character conceived in a truly sincere manner and written in a delicate and fragrant hand."⁵

These Romances represent Clara's mastery of the intimate chamber music style that would define much of her mature output. After Robert's death in 1856, Clara essentially stopped composing, making these among her last creative statements. Modern critics have noted how "lush and poignant, they make one regret that Clara's career as a composer became subordinate to her husband's."

The Romances showcase Clara's evolution as a composer—harmonically complex works that "really draw you in," as pianist Isata Kanneh-Mason observes.⁶ They demonstrate how much Clara had developed beyond her early piano-focused compositions, creating music that speaks with equal eloquence through different instrumental voices.

About the Arrangements

Tonight's performance features several of Clara's original piano pieces arranged for various chamber combinations, and her songs adapted for different instrumental forces while maintaining soprano voice. These arrangements, carefully crafted to preserve Clara's distinctive musical language, allow us to hear her compositions through fresh instrumental colours while respecting the integrity of her original musical ideas.

The adaptations illuminate different aspects of Clara's compositional voice—her gift for melody, her sophisticated harmonic language, and her ability to create intimate musical conversations whether writing for piano, voice, or chamber ensemble. Through these varied instrumental presentations, we can appreciate the full range of Clara's musical expression and understand why her contemporaries, from Mendelssohn to Brahms, held her compositional gifts in such high regard.

Programme notes researched and written by Stephanie Nicholls for Mirabilis Collective.

¹ Review in Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, 1 October 1845.

² Jeffrey Swinkin, "Cyclic Form in Clara Schumann's Four Fugitive Pieces, op. 15," Intégral (2023).

³ Rufus Hallmark, "The Rückert Lieder of Robert and Clara Schumann," 19th-Century Music 14, no. 1 (Summer 1990).

⁴ Susan Wollenberg, "Clara Schumann's 'Liebst du um Schönheit' and the Integrity of a Composer's Vision," in Women and the Nineteenth-Century Lied, ed. Aisling Kenny and Wollenberg (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015).

⁵ Guy Figer, "Three Romances, Op. 22 | Duo Figer-Khanina," Classical Connect, 30 June 2011.

⁶ Isata Kanneh-Mason, interview, uDiscover Music, 6 September 2023.

Artist Biographies

-

Bridget Hutchinson

Piano

-

Lucinda Nicholls

Soprano

-

Ellie Malonzo

Violin

-

Annie Aitken

Narrator

-

Julia Nicholls

Violin

-

Jessica Casey

Viola

-

Elena Wittkuhn

Cello

-

Stephanie Nicholls

Oboe, Piano